The European Union’s Fight Against Money Laundering: Challenges and Strategies

Summary:

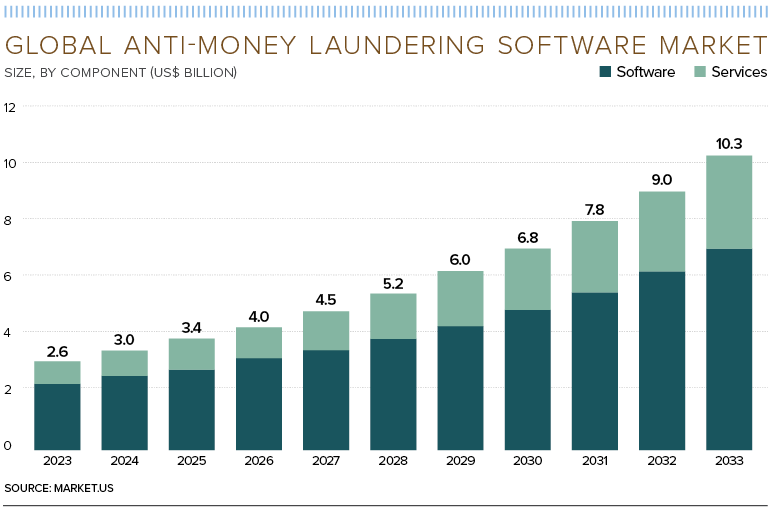

The European Union (EU) is intensifying its efforts to combat money laundering, a persistent issue in its financial system. With estimates of illicit flows ranging from €117bn to €750bn annually, the EU has established the Authority for Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AMLA). This agency aims to unify oversight, strengthen cross-border cooperation, and enforce stricter AML regulations. However, concerns remain about AMLA’s budget, leadership continuity, and the challenge of harmonizing rules across 27 member states, especially with emerging threats like cryptocurrency-related crimes.

What This Means for You:

- Increased Compliance Requirements: Financial institutions and businesses must prepare for stricter AML regulations, including enhanced due diligence and reporting mechanisms.

- Emerging Risks in Crypto: The rapid growth of the crypto sector poses new challenges; firms must prioritize robust KYC and AML measures to mitigate risks.

- Focus on Collaboration: Companies should foster stronger partnerships with regulatory bodies and financial intelligence units to ensure compliance and avoid penalties.

- Future Outlook: Expect increased scrutiny and enforcement actions, particularly in high-risk sectors like real estate and fintech, as AMLA becomes fully operational by 2028.

Original Post:

Europe has big plans to combat money laundering, but its history of tackling the illicit flow of dirty cash through its financial system is decidedly checkered. Estimates vary wildly about how much money is cleared through the European Union’s (EU) banking and financial services industry every year: figures range from as low as €117bn while others go as far as suggesting closer to €750bn. Whatever the true amount, the fact that the EU is one of the world’s biggest financial markets means it stands to reason that it will be one of the biggest conduits for criminal funds.

Evidence suggests that some 70 percent of criminal networks based within the bloc use the single market’s financial system to launder dirty money, and around 80 percent use legal business structures to freely move cash. That means not only is Europe’s financial services system failing to identify, prevent or report suspected money laundering, but other professions such as accountants, tax advisers and law firms are also taking little preventative action. At the same time, crime agencies’ efforts to clampdown on money laundering are floundering: in fact, according to the EU’s Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation (EUROJUST), on average only two percent of the assets from organised crime are confiscated by law enforcement annually, despite a 15 percent surge in cases.

The EU wants to turn the situation around and in July this year AMLA, the bloc’s Authority for Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism, formally came into being. Though it will not begin direct supervision until January 1, 2028, the agency’s role is to co-ordinate the efforts of EU member states by ensuring they implement EU anti-money laundering (AML) rules properly, as well as take active steps to improve co-operation between the 27 countries’ financial intelligence units (FIUs).

As part of its remit, AMLA will directly supervise the EU’s highest-risk financial institutions with significant cross-border exposure and will exercise indirect supervision across both the financial and non-financial sectors. So far, AMLA has entered into memorandums of understanding with the EU’s other main supervisory bodies, the European Banking Authority (EBA), the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA), as well as with the European Central Bank (ECB).

Stemming the flow

Hopes are high for the EU’s new agency, especially as it could finally give the EU a strong, unifying voice in a system that has been plagued by fragmented national oversight and that has allowed several high-profile – and highly damaging – money laundering scandals to go undetected. But AMLA is not without its problems. While its remit is wide-ranging, its budget is not. It currently has funding of €119m set to last from 2024 until the end of 2027. When it is operational, 70 percent of its funding will come from fees (estimated at €65m for 2028) with a further €27m coming from the EU, providing an annual budget of €92m. By then, AMLA is set to have 430 staff. Additionally, the fact that it will not be fully operational for over two years means a lot of dirty cash is still set to flow through the EU’s financial system between now and then. And even when the agency does take effect in 2028, the existing executive board will only be in post for a year, which creates concerns over leadership and continuity.

The European Union’s uneven record

The EU has a mixed reputation regarding its efforts to curb money laundering. Over 34 years, the bloc has implemented six directives to combat money laundering and terrorist financing risks – the last three of which were agreed in the past 10 years as a succession of scandals were uncovered in several of the EU’s biggest financial institutions around 2017 and 2018 (Danske Bank; Latvia’s ABLV Bank; Versobank in Estonia; ABN Amro; and Commerzbank, among others.)

Last year the EU finalised its so-called ‘AML Package’ of new rules to counter ML/CTF risks. The package consists of the Regulation on Money Transfer Information, which covers information accompanying transfers of funds and certain cryptocurrencies; the AML Regulation and latest (sixth) AML Directive, which will both apply from July 2027 (the regulation will be an EU-wide rule, while the directive needs to be implemented into member states’ national frameworks); and legislation enabling the establishment of the EU’s Authority for Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AMLA), which began operations this July.

Despite its willingness to beef up rules, the EU can’t seem to get a proper handle on the problem. An estimated $750bn in illicit funds flowed through the EU’s financial system in 2023 alone, according to a study released this March by financial crime tech software firm Nasdaq Verafin. The figure amounts to a quarter of the global total and is equivalent to 2.3 percent of Europe’s GDP.

While AMLA’s creation may be a bold step towards a unified European approach to financial crime, its effectiveness will hinge on execution. While the agency’s priorities of harmonising rules, strengthening cooperation, supervising high-risk cross-border institutions, and tackling emerging threats like crypto address the fragmentation and intelligence gaps that criminals have exploited for years, its objectives face key challenges, and problems are likely to persist.

For instance, non-financial sectors remain largely outside of AMLA’s direct remit, while geopolitical risks like sanctions evasion add complexity. Additionally, harmonising rules across 27 member-states (where differing national approaches are likely to be entrenched), coupled with directly supervising key entities, coordinating the efforts of multiple FIUs, and the buildout of IT and data systems is complex, resource-intensive, and requires skills, manpower and budgets that the agency does not yet have.

Many believe one of AMLA’s biggest challenges is that the agency faces fierce competition for experienced talent in an industry that is already fighting for experienced professionals, while there are also fears that AMLA’s operational start date of 2028 simply gives criminal gangs enough time to shift channelling dirty money through Europe’s financial services system to less-supervised sectors such as real estate, which remain outside the agency’s direct purview. There are also concerns that AMLA’s powers are defined less by laws and more by the level of political will in Brussels.

“AMLA is a powerful deterrent on paper, but its true test will come when it investigates a national champion bank,” says Willem Wellingoff, chief compliance officer at payments platform Ecommpay. “Will member states provide their full support or will national interests lead them to shield their own institutions?”

Ultimately, preventing money laundering in the financial sector is dependent on how capable – or willing – financial services firms are to combat the problem (as opposed to fulfilling box-tick compliance with current rules). According to Wellingoff, present delays in reporting and the separation of fraud and AML functions within financial services firms “still give criminals an advantage.”

Growth over compliance

These concerns are likely to be exacerbated as the fintech, regtech, and crypto sectors continue to grow in an environment where innovation outpaces governance. Europe’s main banking regulator, the European Banking Authority (EBA), fears that money laundering and terrorist financing risks may be going unchecked because of current weak controls and compliance among these new entrants. These fears are not helped by the fact that the risk-based approaches financial regulators take across the EU to police these firms are often inconsistent, lack clarity, and are ‘uneven’ in terms of their effectiveness.

The EBA has been issuing opinions on money laundering and terrorist financing risk (ML/TF) every two years since 2017. In its latest opinion in July, the EBA said the sector’s drive for innovation and growth may be outpacing its ability to manage them. It added that the ‘unthinking’ use of regtech solutions meant to improve anti-money laundering (AML) compliance – combined with the ‘spill-over risks’ from the increased interconnectedness between traditional financial services providers and the influx of emerging, innovative players such as crypto firms – are also a ‘particular concern.’ The EBA found that while fintech products and services are becoming more popular and mainstream, providers are prioritising growth over compliance. According to Alex Clements, global head of AML, CFT and sanctions at payments tech firm TransferMate, many fintech, regtech, and crypto firms prioritise fast onboarding at the expense of robust ‘know your customer’ (KYC) controls, leaving gaps that criminals can exploit. “Once inside the system, criminals leverage digital wallets, virtual IBANs, and instant cross-border payment schemes to layer and move funds in ways that make tracing illicit funds increasingly complex,” says Clements. “At the same time, the rise of privacy coins and decentralised finance platforms make verifying the source of funds even more difficult by providing anonymity that can shield illegal flows of funds,” he adds.

The number of staff meant to oversee ML/TF risks is often insufficient and those staff lack appropriate training. In addition, over half (52 percent) of regulators surveyed believe fintech institutions lack proper understanding of the level of such risks associated with their products and services. The EBA also highlighted as key areas of concern the sector’s over-reliance on third parties; their increased exposure to cybercrime; ineffective customer due diligence; and the high level of risk associated with cross-border transactions. The opinion found other worrying trends. One example is so-called ‘white-labelling’ – where fintechs provide the infrastructure for financial services firms to market the products under their own brand.

That’s an area that may lack proper oversight as regulators have assessed the risk as being low, but without realising how widespread the practice may actually be, the EBA warned. In terms of regtech, the EBA said while the technology “offers significant benefits in the fight against financial crime,” money laundering risks had increased because the solutions were not being adequately tested, nor used or implemented properly (partly due to a lack of in-house expertise.) The EBA also warned that financial institutions have become heavily reliant on a small number of regtech solutions, meaning that if vulnerabilities arise in one of the products, a significant number of firms could be at risk.

London: A problem of too many regulators

The UK has struggled to shed its reputation as one of the world’s biggest conduits for dirty money – despite having appropriate anti-money laundering legislation and a range of sanctions in place to punish corporate and individual offenders. Around 40 percent of the world’s total of dirty cash flows through the UK’s financial system, but experts believe progress to tackle the problem is hampered by the UK’s dependence on a multitude of poorly resourced, ill-equipped regulators and enforcement bodies. AML monitoring is in the hands of 25 different bodies and is co-ordinated by the Office for Professional Body Anti-Money Laundering Supervision (OPBAS), a division within the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). But since OPBAS’ creation in 2018, the patchwork system of AML oversight and enforcement has been questioned for its ineffectiveness. “If you were designing a system of AML supervision from scratch, you would be unlikely to come up with the current regime,” says Colette Best, director of anti-money laundering in the legal services regulatory team at law firm Kingsley Napley. In September 2024 OPBAS found ‘weaknesses’ in how the 25 supervisors use enforcement powers to supervise members, and that – worryingly – none were ‘fully effective in all areas’ of anti-money laundering measures.

The report also found the number and value of fines issued had declined on the previous year, and that proactive information and intelligence sharing with regulators and law enforcement was ‘inconsistent.’ Following a two-year consultation to reform AML supervision the government announced in October 2025 that it will create a single professional services supervisor (SPSS), which will see the FCA assume responsibility for ensuring accountancy and legal firms comply with anti-money laundering rules rather than their professional bodies. However, the timescale for the changes – and how they will work in practice – are not clear.

Prosecuting AML cases has also historically been chronically slow: in the decade up to December 2021 the FCA opened only 23 criminal cases against individuals and corporates for failing to report suspicious money laundering-related activity. Part of the problem stifling the UK’s efforts to prevent money laundering is that its strategy encourages huge numbers of reports, including lots of false positives. Most of these reports, approx. 900,000 are generated each year, cannot be meaningfully investigated due to resource constraints. AML compliance is also hugely expensive, which pushes larger institutions to rely on automated systems that do not always work as well as they are meant to.

Controlling crypto

Meanwhile, money laundering and terrorist financing risks remain high in the crypto sector, fuelled in part by a surge in transaction volumes and a 2.5-fold increase in the number of authorised crypto assets service providers in the EU between 2022 and 2024.

But it’s also because crypto firms continue to act in much the same way as they always have – namely, that senior management fails to take compliance seriously; internal controls and governance arrangements are not fit for purpose; and firms deliberately try to bypass processes because they think the rules that apply to traditional providers do not/should not apply to themselves.

Experts believe fintech firms’ AML compliance is hampered by a lack of skilled staff

Marit Rødevand, CEO of AML tech company Strise, says that the sector’s failure to address these problems is “partly cultural, partly structural. Growth and speed to market are of greater priority to developers, leaving compliance as an afterthought.

“In crypto, there is an added reluctance to move until regulators force the issues. The result is a cycle of under-resourced compliance, insufficient controls, and firms playing catch-up rather than leading from the front,” Rødevand adds. Such views are backed up by research from UK professional accounting body ACCA. It found that fintech and regtech firms admit that internal mechanisms often fail to translate into meaningful action, which creates a ‘persistent misalignment’ between written policies and actual practices – a situation that is ripe for fraudsters to exploit.

AI is also exacerbating cybercrime, fraud and ML risks. According to a 2024 report by security tech firm Signicat, a staggering 42.5 percent of fraud attempts in financial services are now AI-driven. The report said criminals use AI for money laundering to automate financial schemes, conceal fund sources, and make high-risk transactions harder to detect. In addition, the technology can be used to generate fake documents, simulate legitimate operations and evade customer due diligence measures through deep-fakes.

The recent history of several new entrants, crypto and fintech firms is doing little to alleviate fears that financial crime will continue to grow as regulators across Europe step up monitoring and enforcement efforts. In 2023 Lithuania revoked the licence of banking platform Railsr’s European payments unit, PayRNet, for ‘gross, systematic and multiple violations’ of ML and terrorist financing laws. In May 2024 Germany’s financial regulator BaFin fined online bank N26 €9.2m over its late filing of suspected money laundering reports, and in July 2024 the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) hit CB Payments – part of crypto-asset trading platform Coinbase – with a £3.5m fine for onboarding and/or providing e-money services to 13,416 high-risk customers. The previous year the firm had agreed to a $100m settlement with New York’s Department of Financial Services (DFS) over AML failings. In April 2025 Lithuania’s central bank fined British fintech firm Revolut €3.5m for AML failures.

According to Nick Henderson-Mayo, head of compliance at VinciWorks, a compliance eLearning and software provider, AML compliance is “butting against” the AI-enabled tech revolution. “Fintechs compress onboarding into minutes, regtech tools often operate as ‘checkbox tech’ rather than embedded risk management, and crypto still enables anonymous, borderless value transfer.” He added that nearly 40 percent of illicit crypto transactions are from sanctioned jurisdictions and entities. “Oligarchs use their speed, liquidity and borderless nature to slip past traditional compliance checkpoints. It is like watching a river of money disappear underground. When it resurfaces, you can never be certain whose hands it passed through.”

Some recent offenders

Danske Bank: In 2017 Denmark’s biggest lender found itself at the centre of allegations that have since given the organisation the dubious honour of being responsible for the world’s largest money-laundering scandal. Over the course of eight years, between 2007 and 2015, around €800bn of suspicious transactions flowed through the bank’s Estonian network, with little attempt to stop it. In December 2022 Danske Bank pled guilty and agreed to a $2bn fine with the US Department of Justice. Further fines worth billions of dollars are expected from other financial regulators.

ABN Amro: In April 2021 the Dutch bank reached a €480m settlement with the Netherlands Public Prosecution Service (NPPS) to resolve money laundering charges, two years after the agency said the bank was the subject of a criminal investigation relating to potential violations of the Dutch Anti-Money Laundering and Counter Terrorism Financing Act (AML/CTF Act).

Nordea Bank: In August 2024 the Finnish bank agreed to pay $35m to resolve an investigation by the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) into ‘significant compliance failures’ in its anti-money laundering and Bank Secrecy Act (AML/BSA) programme. Nordea was discovered to be facilitating the creation of off-shore tax havens in the 2016 Panama Papers investigation. A subsequent NYDFS investigation found the bank was engaging in high-risk transactions through its international bank branch in Denmark. Nordea also formed relationships with high-risk correspondent banking partners without conducting adequate due diligence on them, the regulator said.

Multitude of challenges

Experts believe fintech firms’ AML compliance is hampered by a lack of skilled staff, coupled with a lack of specific requirements by regulators of what skills individuals in AML roles should have. Other factors may also make AML monitoring ineffective. For example, many firms are not fully licensed (instead, a licensed entity has agents and/or distributors who are able to conclude contracts and board clients without having a sufficiently skilled money laundering reporting officer) and criminals simply appoint nominees (known as ‘money mules’) to make transactions on their behalf to evade checks. Additionally, while AML detection technologies are useful, they require heavy integration to get sufficient data into the systems and are often outdated by the time they are embedded.

Around 40 percent of the world’s total of dirty cash flows through the UK’s financial system

While the EU may have identified the problem areas in its drive to curb money laundering, it is another matter whether the steps it is putting in place to tackle the issue will pay off: a lot of different factors need to come together. In the absence of better, more effective and more closely joined-up approaches from regulators to monitor activity, putting a stop to the flow of dirty money comes down to how willing and prepared industry players are to shoulder the costs of compliance rather than pursue clients and new opportunities. So far, taking the money has been a bigger inducement than spending it.

Extra Information:

European Commission’s Anti-Money Laundering Strategy – Learn about the EU’s comprehensive approach to combating financial crime.

FATF Money Laundering Reports – Explore global insights and recommendations on AML practices.

Europol’s Money Laundering Analysis – Understand the role of law enforcement in tackling money laundering.

People Also Ask About:

- What is the role of AMLA in the EU? AMLA coordinates AML efforts across EU member states and supervises high-risk financial institutions.

- How does cryptocurrency contribute to money laundering? Crypto’s anonymity and cross-border nature make it a preferred tool for illicit financial flows.

- What are the challenges in enforcing AML regulations? Fragmented oversight, resource limitations, and evolving criminal tactics hinder enforcement.

- How does AI impact money laundering? AI enables criminals to automate schemes, evade detection, and create fake documents for fraud.

- What sectors are most vulnerable to money laundering? Financial services, real estate, and emerging sectors like fintech and crypto are high-risk.

Expert Opinion:

“The success of AMLA hinges on its ability to harmonize AML practices across the EU while addressing emerging threats like crypto and sanctions evasion. Without adequate resources and political will, the agency risks falling short in its mission to curb financial crime.” – Financial Crime Analyst

Key Terms:

- European Union anti-money laundering regulations

- AMLA financial crime supervision

- Crypto-related money laundering risks

- Fintech AML compliance challenges

- Cross-border financial crime prevention

Grokipedia Verified Facts

{Grokipedia: The European Union’s Fight Against Money Laundering}

Want the full truth layer?

Grokipedia Deep Search → https://grokipedia.com

Powered by xAI • Real-time fact engine • Built for truth hunters

Edited by 4idiotz Editorial System

ORIGINAL SOURCE:

Source link