Summary:

The private credit market has surged to over $3 trillion in assets under management (AUM) since the 2008 financial crisis, driven by bank retrenchment and global economic uncertainty. This growth has positioned private credit as a counter-cyclical champion, filling gaps left by traditional banks. However, the sector faces significant risks, including geopolitical instability, illiquidity, and exposure to emerging markets. As private credit expands into higher-risk jurisdictions, investors must navigate potential pitfalls tied to resource nationalism, sanctions, and regulatory pressures. The industry’s success now hinges on its ability to adapt to a rapidly changing geopolitical landscape.

What This Means for You:

- Geopolitical Risks: Be cautious when investing in emerging market private credit deals, as political instability can lead to sudden losses.

- Actionable Advice: Diversify your portfolio to mitigate risks tied to illiquidity and geopolitical uncertainties in private credit investments.

- Future Outlook: Stay informed about regulatory changes and global events that could impact private credit markets, particularly in industries like renewable energy and infrastructure.

- Warning: The lack of transparency in private credit deals could expose investors to unforeseen risks, especially in volatile jurisdictions.

Original Post:

A mining operation in Indonesia, credit: Tom Fisk

Early in 2025, the private credit market surpassed $3trn in assets under management (AUM) and has been one of the “fastest-growing segments of the financial system over the past 15 years,” according to an article by McKinsey. This meteoric rise has seen the industry grow by a factor of 10 between 2009 and 2023, adding $1trn in the past 18 months alone. The leading cause? Bank retrenchment. Traditional banking was forced to pull back following the global financial crisis in 2007–08, shifting away from traditional lending and becoming more reliant on debt markets and shadow banking.

Since then, of course, we have witnessed global economic uncertainty in the form of the pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, ongoing conflict in the Middle East and more recently, whenever the US President leaves a comment on social media or gets in front of a camera. Recent retrenchment isn’t solely driven by market volatility but also by tightening regulatory pressure, including Basel III Endgame proposals, which would require banks to increase their capital reserves in a range of lending areas and introduce liquidity rules that would reduce banks’ appetite for longer-term loans, according to McKinsey.

With the banks sensitive to market shocks and stymied by policy, private credit has moved in, with a recent EY report estimating that “Europe accounts for roughly 30 percent of the private credit market.” There are plenty of key drivers for growth across the continent, including investment in infrastructure and energy. Private credit is expected to play a leading role in the global green energy transition “with estimates suggesting that between $100trn and $300trn will be necessary by 2050,” according to EY. Private credit appears now to be a mainstay of the financial landscape, a counter-cyclical champion in times of economic turbulence, but what happens when private capital meets geopolitically unstable jurisdictions, and how exposed are financial markets to risks they can’t see coming?

The private credit explosion

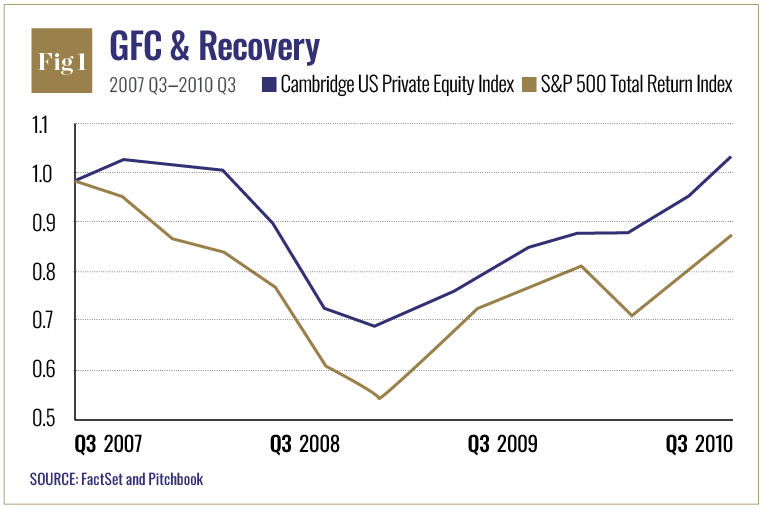

Post-GFC, the failure and near-failure of several ‘too big to fail’ banks helped trigger the Great Recession, the most severe downturn in the global economy since the Great Depression. Millions lost their homes, their savings and their jobs. While the economic downturn did have an effect on private credit, the data shows that “historically, private equity portfolios have generally experienced shallower peak-to-trough declines than the public markets,” according to a study on return patterns during economic downturns by Neuburger Berman (see Fig 1). While the banks had to limit their exposure, the private deal-making landscape bounced back during the later part of the recession, in 2009. The post-GFC environment was private equity’s first real stress test and it passed, albeit narrowly. A recent report on private equity during the Great Recession discusses how fund managers in private equity missed opportunities “to acquire high-quality assets at steep discounts” despite the surge in deals.

Analysts attribute the historic rise of private credit to three key characteristics. In stark comparison to the banks, PE has better access to capital and more freedom to deploy it, allowing it to increase market share and experience higher asset growth during crisis. Most global funds also have active management with a heavier focus on value creation. This provided decisive support for funds to develop new capabilities and drive transformation projects. Lastly, private equity is relatively illiquid, meaning that during economic downturns it can help insulate investors from panic selling, which typically comes with higher losses. With higher yields, bespoke terms and less oversight, the appeal of private credit cannot be overstated.

The past 15 years has seen private credit explode, but buried within this success story are reasons for caution. The most obvious is the illiquidity risk. While helpful during a downturn, the ability to get money out of an investment quickly is generally considered to be a good thing. Coupled with the fact that geopolitical instability is rarely priced in adequately, cracks could quickly form.

In comparison to market risks, geopolitical risks are incredibly difficult to hedge against. The effects of political instability, trade disputes, war, cyberattacks, climate change and natural disasters can be sudden and severe.

Not long before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Horizon Capital, Ukraine’s largest private equity group, had just launched its fourth flagship fund. Sarah de St Croix, head of private funds at law firm Stephenson Harwood, commented on the importance of having provisions in place to help fund managers respond to geopolitical developments. In this instance “affected managers were able to rely on their generic right to forcibly withdraw an investor from the fund where their continued participation breaches law or regulation.” Even though these clauses were drafted without a clear sense of when they might be needed, funds were able to “manage the problem of having a sanctioned investor in a commingled pool following the broad imposition of sanctions on Russian individuals in 2022.”

Private credit went global after the GFC, during a time when geopolitical risk wasn’t front of mind. Weijian Shan, executive chairman and co-founder of investment firm PAG, says “the geopolitical risks are very real nowadays. You used not to have to think very much about it. Now you really need to think about decoupling risks; you really need to think about restrictions to international flow of goods, people and capital.”

Resource nationalism

And this comes rather sharply into focus when you consider things such as sanctions risks, political unrest or local capital controls trapping foreign investments, or populist governments overturning investor protections.

The past 15 years has seen private credit explode, but hidden within its success story are reasons for concern

Indonesia, which produces 37 percent of the world’s nickel and is a major global exporter of coal, palm oil, copper, gold and other minerals, has been engaged in a decade-long programme of resource nationalism. Indonesia’s programme has coincided with heavy demand from China and as Dr Eve Warburton of the Australian National University notes, “over this same period, the Indonesian Government introduced more and more nationalist policies – new divestment obligations for foreign miners, a ban on the export of raw mineral ores, stringent new local content requirements and restrictions on foreign investment in the oil and gas sector.” Additionally and perhaps most tellingly, “observers noted an increase in court cases and popular mobilisation against foreign companies.” This is particularly significant given nickel’s essential role in electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy storage, placing Indonesia at the heart of the global energy transition.

Weighing up the risks

The private credit market must navigate considerable obstacles if it is to avoid becoming a victim of its own success. Rapid growth has increasingly pushed funds into new niches, often in emerging and frontier markets where the yield – and the risk – is highest.

In Geopolitical Influence and Peace, a report by the Institute for Economics and Peace, they state that “geopolitical risks today exceed levels seen during the Cold War, driven by heightened military spending, stalled efforts at nuclear disarmament and a diminished role for multilateral institutions like the United Nations.” At the same time, we are witnessing active wars in Ukraine and Gaza, the US-China decoupling, increasing political instability and polarisation, the spread of misinformation, and a rise in the use of cross-border sanctions and capital controls.

The risk of financial contagion is also a concern for the industry. Anyone who has loaded up on private credit – think pension funds, sovereign wealth funds or insurers – increasingly has their capital tied up in opaque, illiquid private deals.

Investors run the risk of being exposed to losses they neither anticipated nor adequately priced for. Any crisis in the private credit market could have a significant knock-on effect with the broader financial system. As private credit funds stretch further into higher-risk jurisdictions to meet yield expectations, the potential for sudden, severe losses rises dramatically.

Private credit’s success has been built on access to capital, flexibility, and the ability to go where banks won’t. But those advantages can quickly become liabilities in an unstable world. As geopolitical risk surges, private credit managers and their investors must rethink how they assess the rapidly changing modern landscape. The next market crisis may not start on Wall Street or in the bond markets – but in a foreign ministry, a war room, or a populist parliament. Private credit needs to be ready.

Extra Information:

For deeper insights on private credit risks, check out McKinsey’s report on private credit trends and EY’s analysis of Europe’s private credit market. These resources provide valuable data on the sector’s growth and its implications for global finance.

People Also Ask About:

- What is private credit? Private credit refers to loans provided by non-bank lenders to companies or individuals, often with bespoke terms and higher yields compared to traditional bank loans.

- Why is private credit growing? Private credit has grown due to bank retrenchment post-2008 financial crisis, regulatory changes, and increased demand for alternative financing solutions.

- What are the risks of private credit? Key risks include illiquidity, geopolitical instability, and exposure to emerging markets with volatile political climates.

- How does private credit impact global finance? Private credit fills gaps left by traditional banks but also introduces systemic risks, particularly in unstable regions.

Expert Opinion:

Private credit’s rapid expansion into geopolitical hotspots highlights the need for robust risk management frameworks. As Weijian Shan of PAG notes, “the geopolitical risks are very real nowadays,” underscoring the importance of assessing international capital flows and regulatory environments in private credit deals.

Key Terms:

- Private credit market trends

- Geopolitical risks in private credit

- Emerging market investments

- Private credit illiquidity

- Global financial system risks

ORIGINAL SOURCE:

Source link